In this modern era of smartphones containing high-definition cameras, digital images are often presented as evidence in both criminal and civil cases. However, not all images carry the same forensic reliability. A critical distinction exists between a camera original photo and a screenshot of a photo. While a photo captured directly by a camera sensor can be forensically validated, screenshots introduce layers of uncertainty that undermine their evidentiary value. This article explores why courts tend to accept original photographs but should exercise caution, or outright exclusion, when it comes to screenshots.

The primary concern with the production of screenshots as evidence in court is the lack of original metadata.

In a nutshell, metadata in digital photographs is the hidden information stored inside the photo file that tells details about the picture, not just what’s visible in it. It contains background info that helps identify how, when, and sometimes even by whom the image was created. More specifically, the type of metadata typically found in digital images is called Exif data, short for Exchangeable Image File Format, and is a standard format that cameras and smartphones use to save photo-related details automatically. This includes:

- Date and time of capture

- Camera make and model

- GPS coordinates (if location services are enabled)

- Lens settings (aperture, shutter speed, ISO, etc.)

- Unique file hashes (if extracted directly from a device)

Because these data points are generated at the moment of capture by the hardware itself, they provide a verifiable trail. Digital forensic examiners can extract original image files directly from a device using forensically sound practices and specialized tools (e.g., Cellebrite, Magnet AXIOM, Oxygen Forensics). These extractions maintain the integrity of the evidence by preserving metadata and preventing alterations. Once extracted, a photo can be hashed (assigned a unique digital fingerprint) to prove it hasn’t been modified. If challenged, experts can compare the submitted file to the extracted one to confirm authenticity.

Why screenshots are problematic

Screenshots are not camera original captures. They are representations of what appeared on a device’s screen at a given moment, and they lack the trustworthiness of sensor-captured data.

- Photo Details Can Be Misleading – A screenshot records only when the screen capture was taken, not when the underlying image was created. If someone takes a screenshot of a photo from 2018 in 2025, the new timestamp will say “2025,” masking the true origin.

- Context Can Be Altered – Screenshots can show cropped, edited, or staged content. For example, an incriminating text message could be altered in an editing application and then screenshot to hide the manipulation. Additionally, a person or object can be cropped out so the screenshot doesn’t reflect the true circumstances of an event.

- Spoofing Is Easy – Faking or disguising information to make something look real or trustworthy when it isn’t is a simple process on today’s mobile devices. Altered GPS location data, changed dates and times, and application-level modifications can make screenshots appear to contain “authentic” information when they do not.

- Lack of Source Integrity – Unlike original images that can be tied to a device extraction, screenshots sever the link to the source file. There’s no verifiable connection between the screenshot and the original media. It may be critical, for instance, to attribute an image to a specific mobile phone as the original capture device, but the lack of metadata could make this impossible.

- Sanitizing the Metadata – A screenshot would not contain traces of third-party editing applications (i.e. Photoshop, GIMP, or the Photos app which has filters and edit capabilities), which might otherwise appear in the metadata or identifiable text strings within an image file.

Here are some examples of visual and data manipulation which can be sterilized by taking a screenshot of the edited media.

Seen below, the top photo is a camera original that was taken on an iPhone 15 Pro. Below is the edited image which removes one of the cats using a simple method of copy and paste, or cloning, which is very effective in this case due to the random patterns in the gravel. To the naked eye it looks convincing, but the metadata tells a different story.

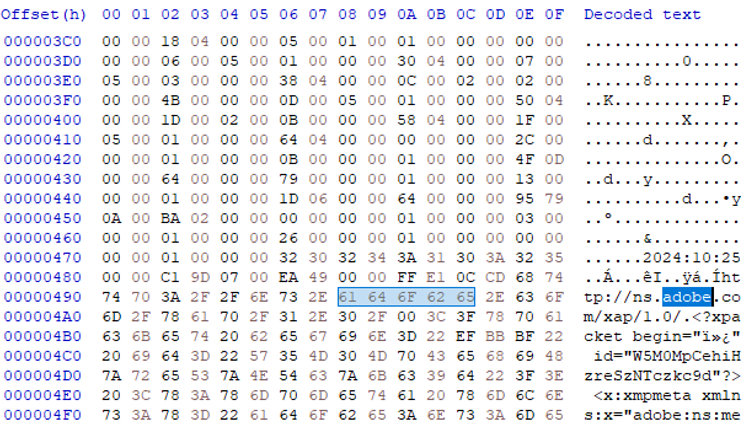

The edited image, when examined with HxD hex editor and the open-source software ExifTool, reveals signatures of third-party applications which would not be present in a camera original. Both Adobe and Gimp signatures are observed, as well as new MAC (modification, access, creation) dates and times

The screenshot of the edited photo, however, is largely absent of metadata and EXIF data seen in the edited camera original. There are much fewer data points identifying the camera make and model, the original time stamp is written over, and there is no GPS data available.

While several forensic methods can help detect image manipulation, such as Error Level Analysis (ELA) and clone detection, their effectiveness is not guaranteed, particularly when global edits or recompression have been applied to the entire image.

Here is another example of how data within an image can be manipulated and misrepresented.

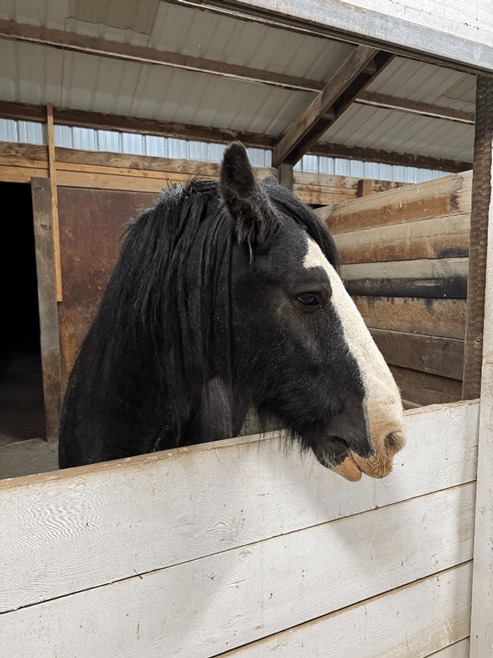

This is my horse, Midnight. He’s a good boy, although he did step on my foot this week and broke a couple of toes.

This photo, also taken with an iPhone 15 Pro, was captured on September 20th, 2025, in Bend, Oregon. But if the screenshot below were presented as evidence, it would imply that the photo was taken on July 20, 2024 in Colorado Springs.

Images such as this are often presented to the court as evidence with the misguided idea that they are providing sufficient proof to support claims of a time or place where a photo was taken by capturing those image details within a screenshot. Quite often they are even further removed from the metadata by being inserted into a PDF document. The essential argument against allowing a screenshot like this to be submitted as evidence is that these values can be changed by the user, and if there were adjustments made to the photo, this would be revealed within the metadata of the original photo. Below is a portion of the metadata as seen within ExifTool.

While the GPS coordinates may be updated within the extracted metadata of the photo, the entries reading “GPS Date/Time” and “Date/Time Created” are significantly different. “GPS Date/Time” shows the moment when manipulations were made, while “Date/Time Created” now reflects the timestamp the photo was edited to show. This discrepancy between dates and times shows that edits had been made, otherwise they would reflect the same values. Without this critical metadata which reveals evidence of manipulation, the court is then then relying on the parties involved to provide additional corroborating evidence to argue that neither that barn nor that treacherous foot-stomping horse were in Colorado on that date.

Furthermore, having access to the original capture device would provide even deeper insight. Performing a full file system extraction on the device would allow an examiner to gain access to certain databases which would provide critical clues as to the history of an image. On an iPhone, edits to a photo’s date, time, or GPS location can sometimes be reverted, as iOS retains the original metadata values within its internal database. This information is stored in the Photos.sqlite database, primarily in the ZASSET (or ZGENERICASSET) table, which holds metadata for each image. These tables act as the backbone of the Photos app’s internal catalog system and contain a wealth of evidentiary information.

Some other key metadata points for an examiner to consider include:

- ZDATECREATED or ZADDEDDATE — the original creation date/time of the image.

- ZCLOUDASSETCREATIONDATE — when the asset was uploaded to iCloud Photos.

- ZLATITUDE / ZLONGITUDE — embedded GPS coordinates.

- ZFILENAME — the actual filename (e.g., IMG_1234.JPG or IMG_E1234.HEIC).

- ZORIGINALFILENAME / ZDERIVEDASSETATTRIBUTES.ZORIGINALFILESIZE — useful for verifying whether the file was renamed, compressed, or re-encoded.

- ZORIGINATINGASSETIDENTIFIER / ZIMPORTEDBYBUNDLEIDENTIFIER — may link to the originating app or device (e.g., “com.apple.camera” vs. “com.apple.messages”).

- ZEDITORID / ZEDITEDFLAGS / ZDERIVATIVE — indicators of edits, crops, filters, or markup applied.

- ZORIGINALRESOURCECHOICE — indicates if an edited version replaced the original in the library.

- ZTRASHEDSTATE / ZTRASHEDDATE / ZTRASHEDBYBUNDLEIDENTIFIER — tracks deleted or trashed assets.

Additionally, the Photos app generally displays images in chronological order based on their recorded creation date, so a purported original photo that appears out of sequence within the gallery could indicate metadata alteration.

Courtroom Implications

Courts require evidence to meet strict standards of reliability and authenticity. Original camera photographs, when extracted correctly, inherently satisfy these requirements because they retain the full, verifiable data generated at the moment of capture, to include crucial elements such as timestamps, GPS coordinates, device identifiers, and other embedded metadata, all of which can be independently verified through forensic analysis. Such features provide a clear chain of custody and a reliable basis for confirming that the image accurately represents the scene or event it depicts.

Screenshots, on the other hand, are derivative, secondary reproductions. They typically do not preserve the original metadata, making it extremely difficult or in many cases impossible to verify the exact time, location, or device from which they originated. Because they can be captured, edited, or manipulated without leaving a clear trace, screenshots carry a higher risk of misrepresentation. Courts should recognize this vulnerability: without corroborating evidence such as server logs, original files, or verified device records, a screenshot alone is generally insufficient to meet evidentiary standards. Presenting a screenshot as primary evidence can therefore jeopardize a case, as it may be deemed unreliable or inadmissible, potentially undermining the credibility of other supporting materials.

In essence, the legal system privileges evidence that can be forensically authenticated, and original photographs hold this advantage over screenshots, which are inherently more vulnerable to tampering, distortion, or loss of context.

Conclusion

The difference between an original camera photo and a screenshot is not trivial. In digital forensic analysis, an original photo is a piece of primary evidence that can be validated through metadata and forensic extraction. A screenshot, by contrast, is secondary evidence, potentially misleading, and highly susceptible to manipulation, and every effort should be made to produce a camera original photo with intact metadata. In the absence of corroborating evidence, such as system logs, metadata, or other verifiable records, a screenshot cannot be authenticated and should not be considered reliable evidence.

For courts, the lesson is clear: trust the source, not the copy.

Leave a comment