Have you ever wondered how many individuals were on a phone call or Facetime call when reviewing data extracted from an iOS device?

This question came up in a case recently when information was developed that multiple calls were said to be group calls. After reviewing the data in multiple commercial and open-source mobile forensic tools, it appeared none of them could answer this question based on the current parsing being done at the time.

Forensic Question:

If the call log of a device reflects a group call, more than two participants, but this data is not currently parsed – where and how is this data being stored within the device? Is this data stored in one location or multiple locations and how can we parse this data?

All SQL queries and artifacts are available for free usage here.

Software Used:

DB Browser for SQLite Version 3.12.2

Magnet AXIOM Process / Examine Version 8.9.0.43012

iLEAPP 2.0.4

CallHistory.storedata:

The location for call log data within an Apple iPhone is the CallHistory.storedata and within the database, there are two tables of focus:

- ZCALLRECORD – which stores the main details of the call, to include: the primary key value (Z_PK), answered status, call type, timestamp of the call, a duration value in seconds, the other participant, country codes, contact names (sometimes), application bundle ID values, etc.

- ZHANDLE – which stores call participant information, namely the primary key value (Z_PK) and the value or phone number.

These tables are well known, and call log artifacts are parsed from these tables. The issue in our case was that processing our FFS Extraction with any tool we could think of was returning calls as direct calls – even when we believed them to be group calls of more than two participants. Based on the parsing and artifact review, there were zero group calls for our dataset and this was not consistent with the facts of the case.

Proceeding Forward:

Briefed on the case details, we devised a plan and started creating test data using multiple Apple iPhone devices. The work was methodical and focused, and each action was initiated on the minute mark.

8:56 AM, Device One FaceTime calls Device Two

8:57 AM, Device One adds Device Three to the FaceTime call

8:58 AM, Device Two adds Device Four to the FaceTime call

8:59 AM, Device One ends the FaceTime call

So on and so forth with incoming calls, all while contemporaneous notes were taken with great care.

The calls continued until 10:06 AM, when the last call was ended. All notes were reviewed to ensure all possible call scenarios thought up during the planning process were complete and documented.

Full File System Extraction:

Satisfied with testing, we initiated a FFS Extraction of one device. The FFS Extraction takes time, and we found ourselves in a post-testing but pre-data review waiting point. Once the FFS Extraction was complete, we initiated processing using Magnet AXIOM Process. Patience is a virtue and an admirable trait but when questions are looming and there are answers to be had, I usually have little of it. But while patience was minimal – options were present.

iLEAPP to the Rescue:

Launching iLEAPP, I added my FFS Extraction, an output location, and selected two modules: Call History (callHistory.py) and interactionC (interactionCcontacts.py) as our initial thought was the interactionC database could shed some light on the data as well. Within minutes iLEAPP ran successfully, I had my report, and I had a data folder in my output location which contained the CallHistory.storedata and interaction.db! (This was considerably faster than waiting for processing to complete and extract out the same databases. Ultimately, the FFS Extraction processing took 2 hours, 9 minutes, and 45 seconds to complete.)

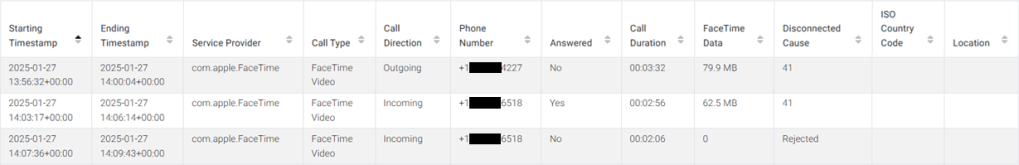

Looking at the iLEAPP report, we saw the following for these three call log artifacts:

How does iLEAPP get you to the data so fast? In short, iLEAPP searches for the input file, the extraction, for all required files based on the modules that have been selected for processing. The required files are placed in a temp location and processed, the processed data is formatted into the html report format, and the source files are available for review in the data folder of your output location.

Reviewing the CallHistory.storedata Database:

Being that most of the data within the CallHistory.storedata database is found within the ZCALLRECORD table, we started there. There was no group call column, no Boolean values of note, nothing that stuck out as being a group call value notation.

All in all, there are not a lot of tables within the CallHistory.storadata database… Quickly one stuck out, namely the only table beyond the ZCALLRECORD and ZHANDLE tables to have considerable data – the Z_2REMOTEPARTICIPANTHANDLES table. And, for a table that had more rows than either our ZCALLRECORD and ZHANDLE tables, it did not have a lot of columns – Z_2REMOTEPARTICIPANTCALLS and Z_4REMOTEPARTICIPANTHANDLES.

The significant data here is subtle but it is there:

| Z_2REMOTEPARTICIPANTCALLS | Z_4REMOTEPARTICIPANTHANDLES |

| 1776 | 1811 |

| 1778 | 1812 |

| 1778 | 1813 |

| 1778 | 1815 |

| 1779 | 1816 |

| 1779 | 1818 |

| 1780 | 1820 |

| 1780 | 1819 |

| 1781 | 1822 |

| 1782 | 1825 |

These columns can be explained as calls and participant handles – which is also how the table joins work.

LEFT OUTER JOIN Z_2REMOTEPARTICIPANTHANDLES ON Z_2REMOTEPARTICIPANTHANDLES.Z_2REMOTEPARTICIPANTCALLS IS ZCALLRECORD.Z_PK

LEFT OUTER JOIN ZHANDLE ON Z_2REMOTEPARTICIPANTHANDLES.Z_4REMOTEPARTICIPANTHANDLES IS ZHANDLE.Z_PK

But, in viewing our calls table we can see repeated values – 1778 references three unique handle values and 1779 and 1780 reference two unique handle values.

In our query, we leverage a GROUP_CONCAT() aggregate function which can combine multiple values from different rows into one string. Using GROUP_CONCAT(Z_2REMOTEPARTICIPANTHANDLES. Z_4REMOTEPARTICIPANTHANDLES, ‘, ‘), we would arrive at the following:

1812, 1813, 1815

1816, 1818

1820, 1819

Using GROUP_CONCAT(ZHANDLE.ZVALUE, ‘, ‘), as we do in the full query, we instead receive the contact numbers of all participants on this call.

Updating our query with GROUP_CONCAT functions and new JOINs we get the following:

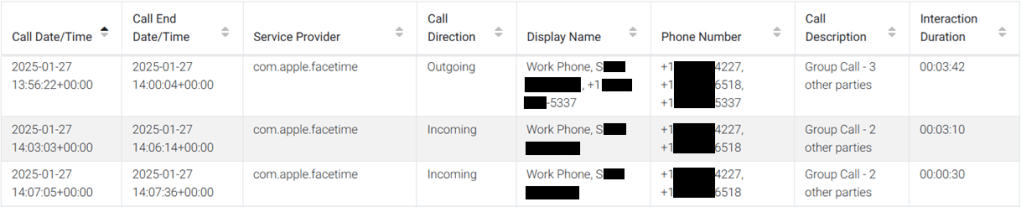

interactionC Data Yields:

Through our testing and scripting, this data was also present within the interactionC.db – albeit the timeframe is not as long. The CallHistory.storedata data was present for just under two years, while the interactionC.db data was present for about six months within the reviewed dataset. Still, looking at the interactionC.db values for these same calls it serves as a validation of the CallHistory.storedata artifacts. Not all column data is stored in the interactionC.db and an example output for these same calls is as follows:

Conclusion:

Within this article, we highlighted the challenges and solutions in analyzing group call data from iOS devices, where traditional forensic tools may fail to accurately parse such information. Through careful testing and data review, we uncovered how group call data is stored and can be retrieved. By leveraging advanced queries, we successfully extracted and validated participant details for group calls that were not readily apparent. This case emphasizes the importance of adapting forensic methods to uncover hidden data and provides valuable insights for professionals working with mobile device forensics.

Leave a comment